Illinois Legislature Passed Marriage Equality Bill

Illinois shall become the 15th state to recognize same-sex marriage. When Governor Patrick Quinn signs the bill, LGBT couples may become lawfully married on June 1, 2014. See the live vote and Illinois Representative Greg Harris\’ remark, here.

The IRS Takes a Bite Out of DOMA, Pt 2

As mentioned in the first article of this series, the U.S. Supreme Court’s (aka SCOTUS) Windsor decision resulted in a flurry of guidance from several government agencies. The agency leading the charge, because its treatment of estate taxes was called to the carpet in Windsor, was the IRS. Sidebar: When SCOTUS or an agency, such as the IRS, decides on an overall course of action, the action typically can’t or, better yet – shouldn’t, occur until the agency provides a legal how-to analysis and procedural guidelines (aka “guidance”) for those who depend on the agency when performing their respective jobs. In this case, it would be estate planners, CPAs, and others. The IRS responded to Windsor faster than most of us have ever seen with respect to an issue of discriminatory treatment of individuals; it’s response was Revenue Ruling (Rev. Rule) 2013-17. WARNING: Despite my best efforts the following language will likely be a little dry. Rev. Rule 2013-17 painstakingly crafted an IRS rule based on (1) gender neutrality, (2) the IRS’s historical treatment of common law marriage, and (3) the burdens placed on both the taxpayer and the IRS by the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). Though somewhat spliced between most sections of the analysis, the rule provides that in the eyes of the IRS, “husband,” “wife,” and “spouse” each mean a “married person” and that “marriage” is a lawful union between “married people.” Thus, the Rev. Rule completely removed gender from the analysis of tax treatment for married couples. The IRS reached this conclusion by examining the references to gender within the Internal Revenue Code (Code) itself and found few instances of express, gender-specific terms. Further examination of legislative history and recognition of statutory construction (how laws should be interpreted) supported the gender neutrality basis for the federal tax treatment of married same-sex couples. Next, to answer whether credence should be given to state law if the state didn’t recognize the marriage as valid (recall, SCOTUS didn’t invalidate DOMA Section 2 which allows a state to not recognize valid same-sex marriages), the IRS considered its historical treatment of common law marriages. More than 50 years ago, the IRS decided that it would recognize common law marriages even if a state didn’t; therefore, it saw no reason to undo more than 50 years of precedent. (I will resist the strong temptation to comment on Citizens United here.) Equally important, the IRS determined that despite the lack of uniformity among the states regarding marriage and state taxes, “uniform nationwide rules are essential for efficient and fair tax administration.” Considering how inefficient DOMA Section 3 made tax administration, the IRS stated that “more than 200 Code provisions and Treasury regulations” contain terms pertaining to marriage. Additionally, more than 1,000 statutes and regulations are affected by DOMA, placing a huge burden on same-sex couples by forcing them to use a complicated tax return filing process. Finally, the IRS also recognized the increased healthcare costs to these families created by a loss of the tax benefits opposite-sex spouses enjoy though employer benefits. Also, looking at DOMA and its Section 3’s affect on tax administration, the IRS pointed to Windsor, where the reason for Section 3 was noted as anything but fair but, on the contrary, designed to “injure and disparage” same-sex couples seeking to marry. The Rev. Rule also acknowledged and agreed with SCOTUS\’s Fifth Amendment analysis inWindsor, stating that the IRS would prefer to pass rules and regulations that are more constitutionally valid than not. Accordingly, the IRS per Rev Rule 2013-17 affords legally married same-sex couples the same tax treatment with respect to the federal tax regime as married opposite-sex couples, even if the couple resides in a state that doesn’t recognize their marriage (an “unfriendly” state). The rule, however, also expressly provides that this treatment does not extend to those couples in a Civil Union, Registered Domestic Partnership, or other relationship that bears a substantial similarity in state law benefits to marriage but are not, in fact, marriages. IRS v. DOMA: IRS score BIG ONE; DOMA down 1 ½ . Tune in next week for what this means practically speaking for married LGBT couples. The IRS Bites DOMA, Pt 1 | 2 | 3 | 4

The IRS Takes a Bite Out of DOMA, Part 1

Recently, on a panel at a Chicago Bar Association’s Trust Committee meeting, I discussed tax and estate planning issues in light of the U.S. Supreme Court case, U.S. v. Windsor and the new federal agency rules on same-sex married couples. This article is Part 1 of a 4-part series from that discussion. Before Windsor, preparing estate plans for same-sex couples was often complex, especially if the couples were married, in a Civil Union, Registered Domestic Partners, or long-time partners in a substantially similar relationship when compared to opposite-sex married couples. The so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) compounded the complexity by prohibiting federal agencies from recognizing the couples and spurring states to create mini-DOMAs. The disparate treatment forced same-sex couples with sizable estates to literally give away large portions of their assets, either in the form of charitable donations or tax payments. However, even couples with very modest estates were required to have powers of attorney and related directives prepared with painstaking creativity. Finally, when most couples, despite their estate\’s size, asked why their planning was so complex, they listened to how their families were “different” and warnings, such as “though a valid legal document, don’t use this in Texas,” or “don’t have an accident in Will County.” Generally, creating a joint will for same-sex couples, even those lawfully married, was and still is a risky undertaking because the relationship was not federally recognized and is not recognized by a majority of states. Even in states such as Illinois where Civil Union couples have the same benefits of as opposite-sex married couples, including testamentary benefit, some counties are nonetheless hostile. Thus, a surviving partner presenting a joint will in a probate court of such a county might face an uphill battle. Setting the issue of joint wills aside, but considering will provisions, the unequal treatment of same-sex couples required careful tailoring of what could be boilerplate provisions in wills for opposite-sex married couples. The tailoring and special provisions include: Family Article; A statement of intent; Definitions providing expansive and inclusive meanings for “child,” “partner,” Civil Union, Registered Domestic partner, spouse, next of kin, and marriage; Prospective guardianship and successor guardianship language; A no-contest provision; A pour-over provision; A definitive choice of law statement; A notary seal, though notarizing a will is not required in Illinois; and more. I mentioned the pour-over provision because even if the family is of modest means, contentious behavior from another family member would warrant a trust also be prepared as a second line of defense for fighting contention. This is not the case for married opposite-sex couples because the opposite-sex surviving spouse would, at least initially, have the law squarely on his or her side as a second line of defense. If a same-sex couple of modest means could not afford a trust, and some could not, then they would try to plan for transferring all assets by operation of law and hope that a family member with a small estate affidavit didn’t show up to claim for the forgotten bank account. For the sake of example, let’s say a trust was prepared. One positive sliver for practitioners and our clients was that we didn’t have to worry about the reciprocal trust doctrine or unlimited marital deduction (IRC 2056) issues. But that was just the point: Because of the unfair treatment by the government, our clients could not take advantage of the unlimited marital deduction, federal QTIP elections, gift-splitting, or portability. So provisions had to be drafted carefully to work-around this lack of spousal gifting benefits. Additional provisions and mechanisms for trusts included: Expressly prohibiting a contentious family member from acting in a fiduciary capacity Providing the trustee and successor trustee with HIPAA rights; Providing the trustee with authority to take reasonable steps to ensure transfer of retirement assets to the same-sex spouse or partner result in the least adverse tax implications for the surviving spouse or partner; Using life insurance trusts; and Thoughtfully and diligently considering the “common disaster” provision. As mentioned earlier, other directives, agreements, and documents were and still are critical. These instruments include HIPAA release forms; a hospital visitation authorization form; reciprocal powers of attorney with 2 disinterested witnesses per instrument and with each instrument notarized but with a warning about describing the relationship depending on the county (imagine – having to hide your relationship in case of a medical emergency in order to ensure your spouse’s medical treatment!); reciprocal living wills; and reciprocal Illinois Mental Health Treatment Declarations. Many colleagues might say that possessing all of these documents would be redundant, and they would be correct…with respect to opposite-sex married couples. However, for same-sex married couples possessing all of these documents is evidence that strongly supports the commitment between the 2 individuals and, thus, their testamentary intent. Thankfully, Windsor and the subsequent flurry of guidance from government agencies took a bite out of DOMA; and stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, which will cover that guidance. One nation with justice and liberty for all… The IRS Bites DOMA, Pt 1 | 2 | 3 | 4

Dueling Executors

Frequently, I answer questions on Avvo about estate planning and related topics. A little while ago, someone asked a question about the validity of a will that was “poorly written” and disputes between co-executors. This article expands on that answer. A will is considered invalid if its \”formalities\” are not followed. The formalities are that the will be signed by 2 credible witnesses while in the presence of a legally sound adult testator (person who makes the will) when he or she signed the will. So, Skyping or video signings are not allowed, at least in Illinois. In addition to being credible, witnesses must also be adults and “disinterested.” A disinterested witness is one who is not a beneficiary, either primary or contingent, under the will. If a potential beneficiary or the spouse of a potential beneficiary acts as a witness, then 3 witnesses should be used. Sometimes it is difficult to equally divide estate assets to an exact amount, which is why attorneys use \”substantially equal\” or \”as equal as possible\” with respect to distribution language. Presuming a disputing co-executor has a copy of the will, the will’s terms should define how disputes between co-executors should be handled. If the will is silent on that issue, then a case of breach of fiduciary duty may exist because an executor, even if also a beneficiary, has an obligation to all of the beneficiaries, not just himself of herself. However, Illinois courts have started looking very closely at the terms of the instrument and the facts surrounding disputes. Additionally, courts are interpreting wills and trusts from a contractual perspective, going so far as to state one executor did not have a fiduciary duty. Thus, breach of fiduciary duty may now be a very difficult claim to successfully make. A will is typically invalidated on grounds of undue influence, i.e., someone took advantage of the testator’s mindset while he or she was making the will, or other similar grounds. A validly executed but poorly written will is not a reason to invalidate the will as a whole. Even if a provision of a will is deemed invalid, a court will likely strike the provision as invalid but maintain the validity of the rest of the instrument. Feel free to check out my Avvo answers on our website.

The IRS Recognizes Your Marriage Even if Your State Won\’t

Last week, in the wake of Windsor v. U.S., the IRS issued Revenue Ruling 2013-17. A Revenue Ruling, or “Rev. Rule,” is similar to a court opinion; it\’s just IRS law instead of case law. Thus, Rev. Rule 2013-17 mandated equal tax treatment for all lawfully married same-sex couples in ALL of the United States of America. As discussed here previously, in Windsor, the Supreme Court struck down Section 3 of the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which provided that the definition of marriage for purposes of rules, regulations, and laws promulgated through the federal government was the legal union of one man and one woman as husband and wife. The Windsor decision was a great step forward in ending discrimination against a segment of the U.S. population; however the decision was incomplete because it left standing DOMA\’s Section 2 that provides that states do not have to recognize same-sex marriages. As a result, Windsor v. U.S. left an even messier patchwork of laws for states and the federal government to wrestle with in regards to marriage equality. The question in Windsor was whether the IRS wrongfully denied issuing an estate tax refund requested by the surviving spouse of a married same-sex couple. The IRS lost in the lower court and SCOTUS affirmed that court\’s decision by striking Section 3. Having not prevailed, the IRS then had to determine how to comply with the Court Order. Had the IRS decided that tax return filings were to be based on domicile, then it would have been aligned with Section 2 of DOMA. Same-sex married couples residing in “unfriendly” states would have had to ignore the fact that they were legally married and file as “single.” So the IRS could still have chosen a less than friendly route for same-sex marrieds. However, recognizing the spirit of Windsor, Rev. Rule 2013-17 mandated equal treatment of married same-sex couples by basing the filing of returns on place of solemnization: \”For Federal tax purposes, the [IRS] adopts a general rule recognizing a marriage of same-sex individuals that was validly entered into in a state whose laws authorize the marriage of two individuals o the same sex even if the married couple is domiciled in a state that does not recognize the validity of that same-sex marriage.\” (Emphasis added.) What exactly does this mean overall? It means that lawfully married same-sex couples can live in unfriendly states and file taxes for the federal government using “married filing jointly” or “married filing separately.” Unfortunately, they still must abide by state tax return rules but at least they don’t have to move. What does this mean for same-sex couples in Illinois? If you were legally married elsewhere, e.g., Iowa, but reside in Illinois, you can file federal and state taxes using your legal relationship status and file “married filing jointly” or “married filing separately.” If you are in a Civil Union, you can\’t file your federal taxes as a married couple but you can file your state taxes as a married couple. Agreed: Illinois needs to get with the program and provide marriage equality. Summarily? While SCOTUS purportedly left the issue of validating same-sex marriage to the states, at least some federal agencies, such as the IRS, that actually must perform the work SCOTUS decisions create, recognize the \”United\” in U.S.A. and are willing to pass laws accordingly.

Unraveling the Windsor Knot Part II

In Part I, we covered the U.S. v. Windsor (Windsor) analysis on the first component of standing: Article III requirements. Standing is the term of art used to discuss whether (1) parties have a case or controversy that the courts can hear, i.e., “Article III standing,” and (2) even if the court can hear the case, after considering other factors, the issue becomes should it, i.e., “prudential standing.” Here, in Part II, we continue looking at the issue of standing, specifically, satisfying the prudential principle. HINT: If you don\’t want to fight through the necessary legalese, bullet points are at the end. Having found Article III standing requirements met, the majority in Windsor, continued to prudential considerations. The Opinion used prudential considerations to address the BLAG’s standing. Before discussing and explaining what prudential standing is, Justice Scalia’s reference in his dissent to the majority’s use of prudential considerations is worth noting. Scalia argued that that majority sees the Article III requirements of adverseness as “prudential.” Recognizing how the Court uses the term “adverseness” in the Opinion, one can understand Scalia’s observation that the majority conflates adversity within the meaning of controversy for Article III standing and the adverseness involved with prudential standing. The majority cites Allen v. Wright (Allen) to explain the principle of prudential standing and offers Warth v. Seldin (Warth) as an example of how the limitations considered in the prudential principle can be overcome. And it is with these 2 cases that we’ll continue untying the Windsor knot of standing. Allen is a 1984 case where African-American families challenged the IRS’ standards for tax-exempt status as those standards were applied to private schools that allegedly engaged in racial discrimination. The Court in Allen, stated that the prudential strand of standing called for “judicially self-imposed limits on the exercise of federal jurisdiction, such as (1) the general prohibition on a litigant\’s raising another person\’s legal rights, (2) the rule barring adjudication of generalized grievances more appropriately addressed in the representative branches (a little ditty known as the “political question doctrine”), and (3) the requirement that a plaintiff\’s complaint fall within the zone of interests protected by the law invoked.” So this means that even if Article III standing is found, an appellate court does not have to hear a case if it is limited by one or more of the 3 factors listed above, i.e, if the Court is limited by prudential considerations. Ultimately, the Court ruled that the plaintiffs in Allen lacked Article III standing. Since the plaintiffs lacked Article III standing, whether the plaintiffs had prudential standing was irrelevant. The Court also made clear that an individual’s mere assertion of a right to have the federal government act in a way that is lawful is not sufficient to have a case heard. Warth, decided in 1975 – before Allen, involved taxpayers, residents, and a non-profit organization of Rochester County, New York that opposed zoning laws preventing low and moderate income families from being able to live in Penfield, NY. Proponents of the zoning laws were Penfield’s town, its Zoning Board, and Penfield’s Planning Commission members. The Court in Warth, first elaborated on Article III standing requirements and found them unmet but still considered prudential limitations, stating that “countervailing considerations … may outweigh concerns underlying the usual reluctance to exert judicial power.” So while Article III standing is required and prudential limits can veto Article III standing, certain factors can also veto prudential standing. In the same analysis structure as Warth and Allen, the Court in Windsor first considered Article III requirements, which the Court found satisfied. Then the Court considered the prudential limitations and found that sufficient “countervailing considerations” outweighed prudential limitations. This, Justice Scalia found, “incomprehensible.” But Scalia failed to mention that if the Court’s discussion in Windsor is viewed en toto, the Court is undoubtedly considering the 2 components of standing as separate components: Article III standing as explained in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife and (2) prudential limitations as explained in Warth and Allen. In fact, the majority stated outright, “The Court has kept these 2 strands separate: “Article III standing, which enforces the Constitution’s case-or-controversy requirement [citation omitted]; and prudential standing, which embodies “judicially self-imposed limits on the exercise of federal jurisdiction.” However, using the terminology generally ascribed to one principal as a way to explain how the other principle is applicable is assuredly confusing. And Justice Scalia\’s comments, in typical Scalia form, magnify the confusion. Forgetting Scalia’s commentary, the explanation in Warth clarifies the Windsor Opinion’s take on prudential limitations. Warth explains that if a plaintiff’s claim affects the legal rights of third parties, then prudential limits that might generally apply may be set aside. In other words, protecting the legal rights of persons outside the immediate parties involved might be more important than denying relief to one, as long as Article III requirements were met. In Windsor, Edie’s “win” wasn’t really a win because the IRS still refused to refund her money. So there was Article III controversy. Equally important, DOMA, a congressional statute negatively affected the rights of hundreds of thousands of others. It was this negative effect, which the majority called “adverseness,” that met the Warth test for overweighing the prudential considerations to which the Windsor majority referred in its prudential principle discussion. Justice Scalia chided the majority for calling \”adverseness\” an element of standing, when, in fact, per Chadha v. INS (Chadha) and Baker v. Carr (Baker), the adverseness that the majority refers to is provided to support an argument for prudential standing. Furthermore, Scalia projects the majority’s use of prudential standing in Chadha onto the majority’s use in Windsor, when it is not the use of prudential sanding as it was used in Chadha but the underlying factors of prudential standing that the majority used in Windsor. Again, by stepping back a few paces and analyzing the majority’s discussion as a whole, Baker also illuminates the issue and provides foundation for the Warth explanation. Baker

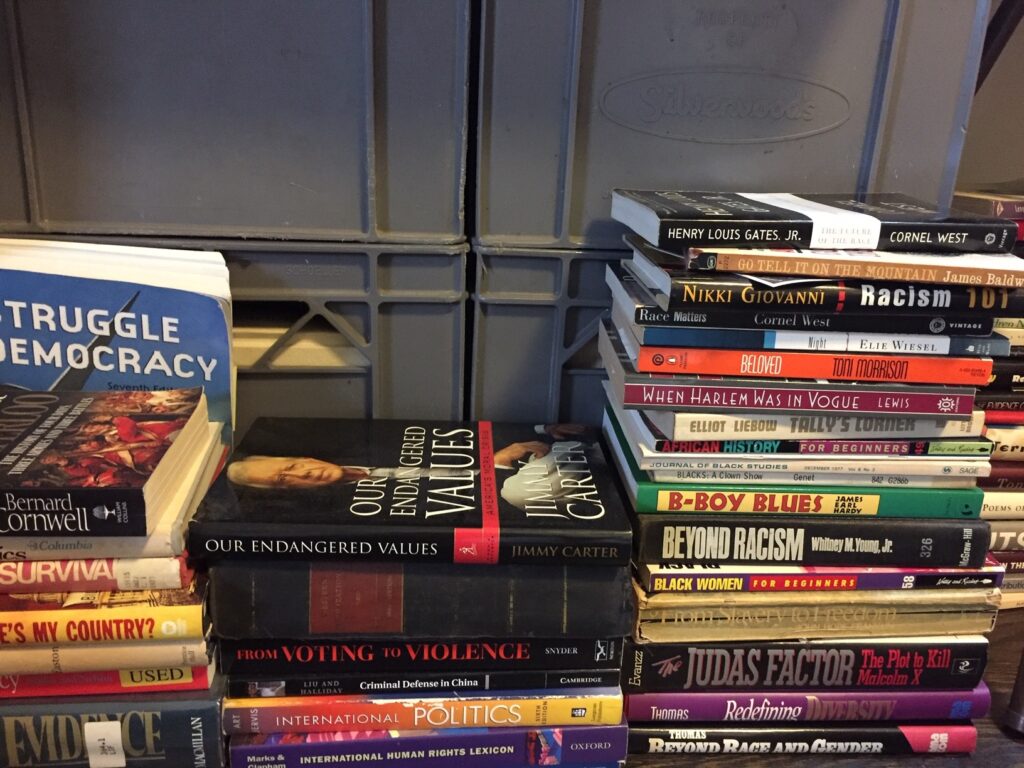

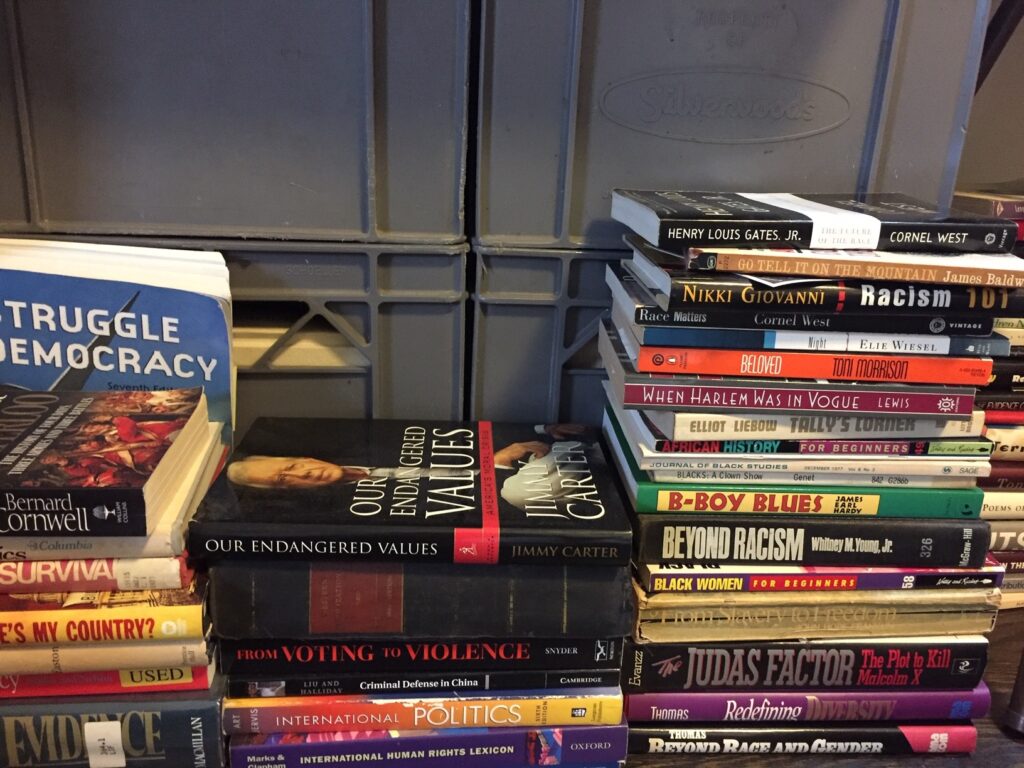

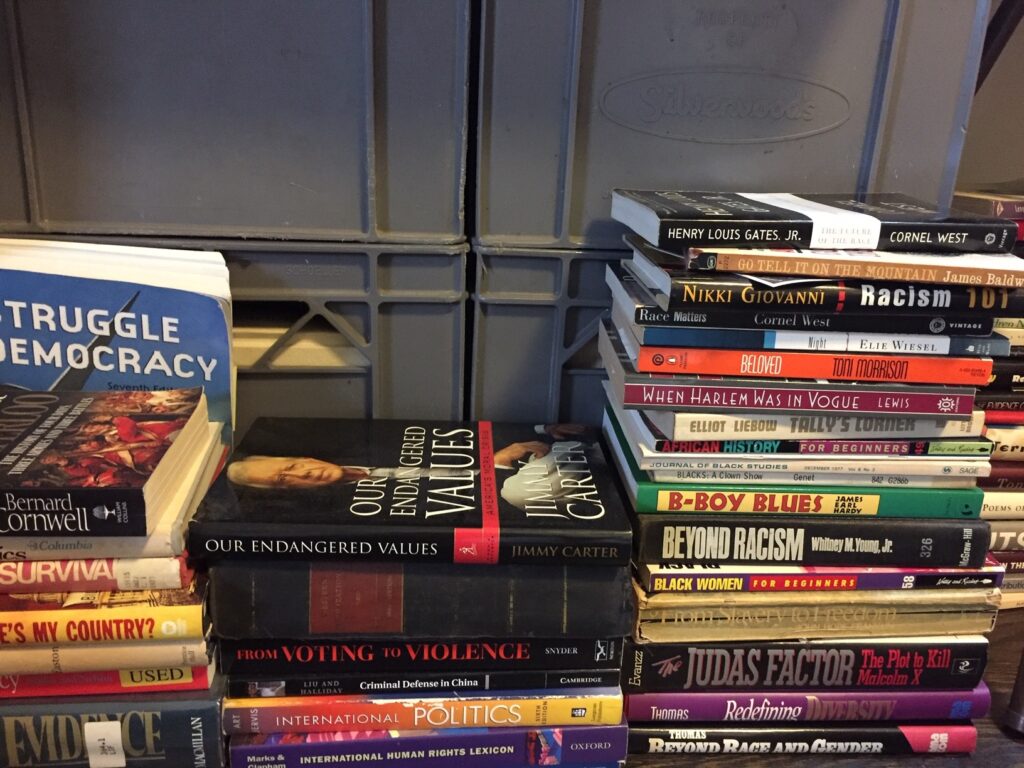

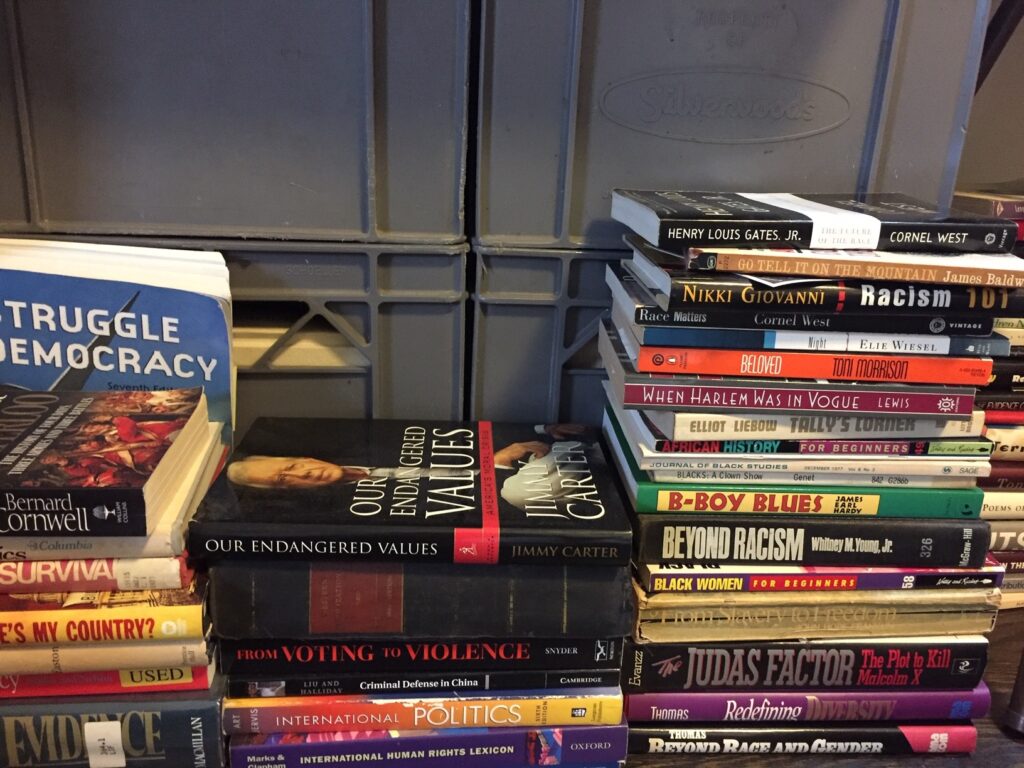

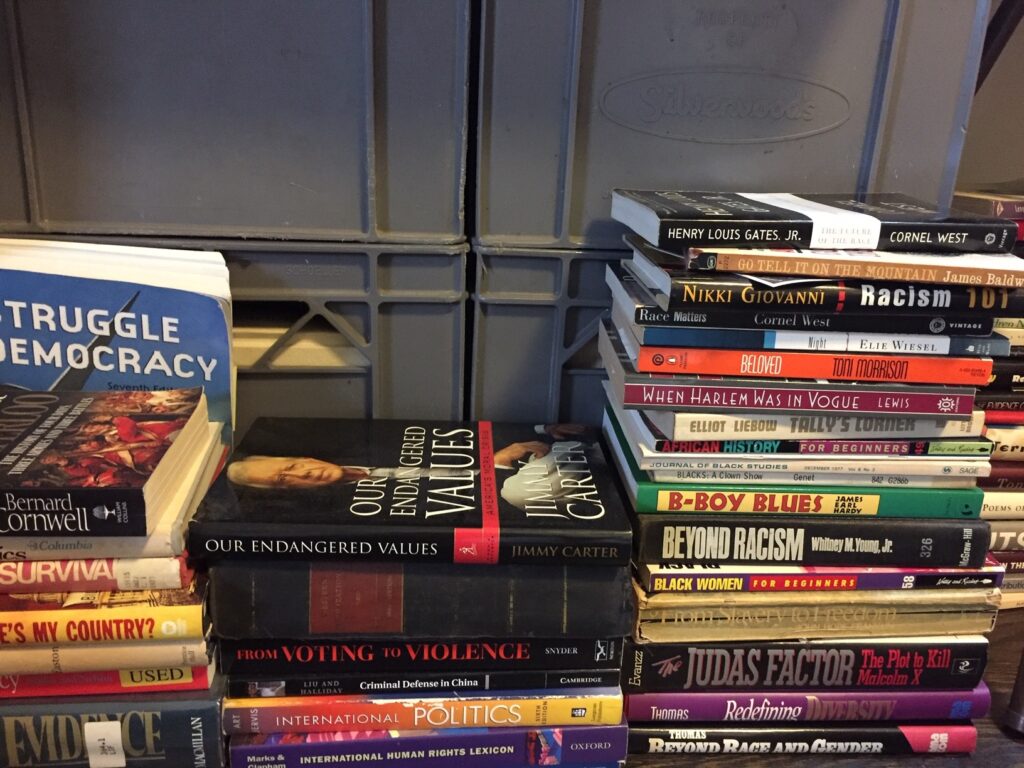

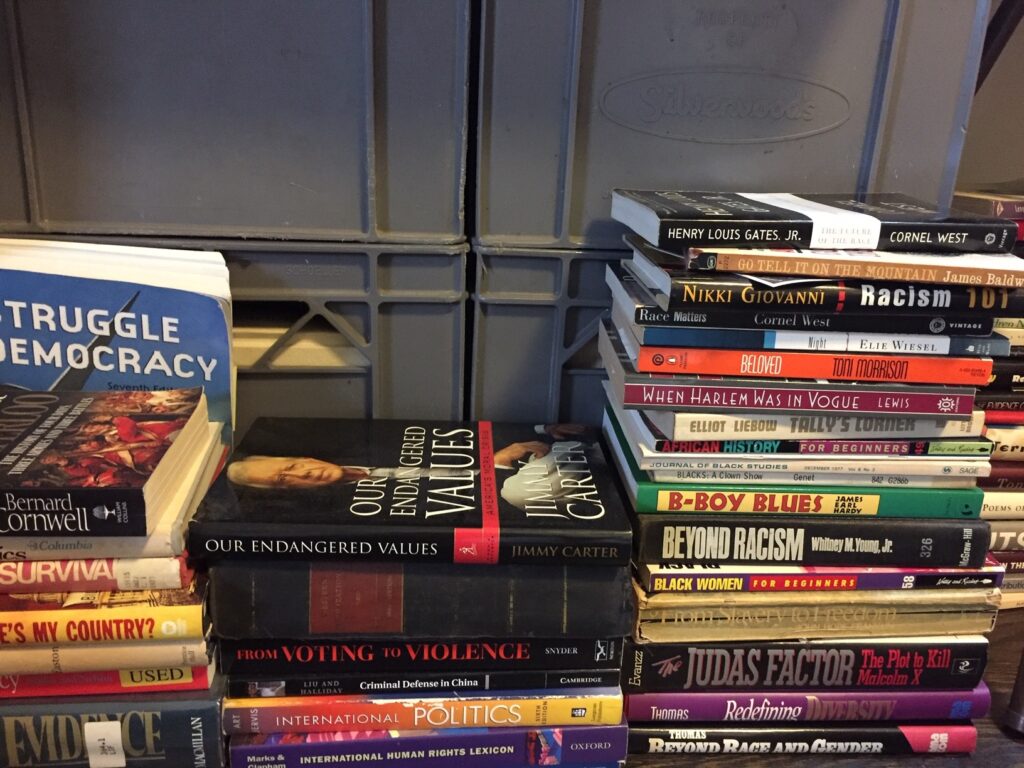

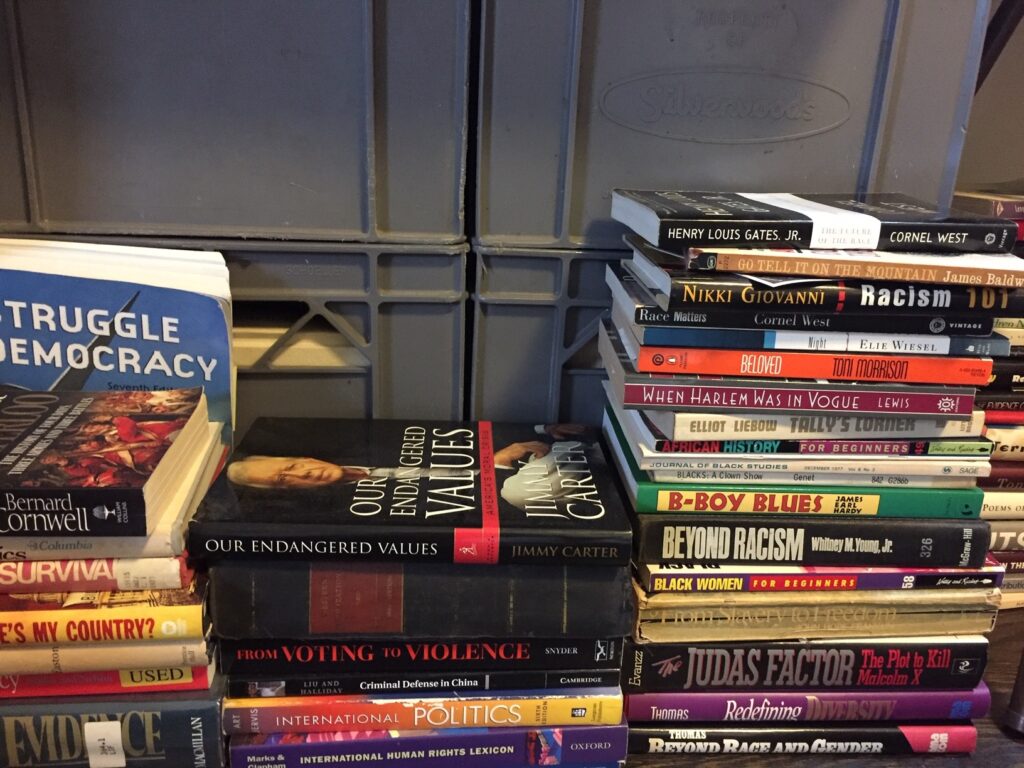

Important Digression from Windsor Analysis – Still Civil Rights

I recently posted the following on my personal Facebook page because it was Sunday and I don\’t work on Sundays. However, because I am an African-American, female, lawyer, an example of the mixed ideals that can be realized, and have experienced first-hand how those ideals can be jeopardized by hatred and ignorance, I am compelled to share it here: May we all recognize that our country, the United States of America, has yet to be free from the tentacles of hatred, racism, sexism, and all the ugly isms that comprise the darker side of humanity. These tentacles pervade every system that we and our children depend on, including the \”justice\” and \”educational\” systems. This summer, Americans witnessed the turning back of civil rights to the days where: it was acceptable to kill, rape, or beat someone because of the color of their skin or their gender; it was acceptable to preclude citizens from voting because of the color of their skin; it was acceptable to treat women as objects to be used and discarded in employment because men could not control themselves; and it was acceptable to erect and sustain barriers to educational equality for people of color. So, sadly, let us recognize that the days of uplifting the whole of our country, where equality for all instead of economy for some was the objective and seen as a duty of most of our citizens, is over. Some of us will continue to fight for equality but many of us will not even when the U.S. spells \”us.\”

Unraveling the Windsor Knot

Last week’s lengthy post examined from a broad perspective the United States v. Windsor case as a whole regarding what it did and did not do for same-sex marriage in the U.S. This week’s post is the first in a series of closer examinations on the specific issues and case law involved in this “landmark” Opinion. Though, the phrase “earth-shattering” may be more appropriate. In this first more narrow perspective, we’ll start with the Court’s question on whether it should have heard the case at all, particularly the issue of Article III jurisdiction. Article III of the U.S. Constitution mandates that courts can only hear “cases” or “controversies” and case law adds a few other requirements. So let’s consider how the question of Article III jurisdiction came into play and how it was resolved. Controversies may seem readily apparent simply because one party is on one side of the “v,” for “versus,” and another party is on the other side, e.g., United States Versus Windsor. Obviously, the U.S. and Windsor disagreed. But did they? Those who say no genuine controversy existed based their argument on the fact that the Department of Justice refused to defend DOMA’s Section 3 because the President considered Section 3 unconstitutional. Can the President do that? Yes, the President can and the United States Supreme Court agreed with the Constitutional scholar who is also the President of the United States of America: Section 3 of DOMA is unconstitutional. BUT, the sticky wicket in this case was that the Executive typically takes this type of position when the situation is adversarial, i.e., when a lower court disagrees. In Windsor, the lower court agreed. So just how was there was a “controversy”? Well, the Executive may have refused to defend Section 3, but it stated that it would continue to enforce it. A la, we have controversy…maybe… The Supreme Court used the case, Hein v. Freedom From Religion Foundation, as its starting point. In Hein, taxpayers sued the government for using money in faith-based programs initiated by former President Bush. The Court determined that the taxpayers lacked standing and thus couldn’t sue and reversed the appellate court’s ruling. A fundamental requirement for Article III controversies is standing, which is met when “a plaintiff [alleges] personal injury” that can be reasonably liked back to the defendant’s illegal action or actions and the relief sought by the plaintiff can probably be provided. Here, there was no doubt that Edie suffered injury – more than $360,000 worth – and the U.S. wasn’t going to enforce the IRS’s refusal to pay the refund based on DOMA’s Section 3. So, though the lower court may have ordered the IRS to pay, congressional law told the IRS not to refund the payment. The Court probably could have stopped here, because it could have remanded the case back down to the lower court with the admonition, with which Justice Scalia would have agreed, that Congress already spoke. But the Court ventured on, using INS v. Chadha to find controversy in the case past the issue of remand. In Chadha, a person who overstayed their visa was ordered by the INS (now known as USCIS) to leave the U.S. That person appealed to the Attorney General of the U.S., who granted the relief. However, Congress had the authority to veto the U.S. Attorney General and did so. So, like Windsor, Chadha was a case where the Executive sided with one plaintiff and another government body – this time the House – disagreed. The Court in Chadha ruled that a controversy existed despite the agreement because there was “concrete adverseness\” about the issue and there was adequate Article III standing before Congress vetoed. Now, let’s look at Windsor again. The lower appellate court and the plaintiff agreed in Windsor agreed. There was – and still is – an ugly, discriminatory congressional statute affecting “the entire U.S. Code.” So Congress had spoken. These facts are a tad different from Chadha… So where’s the controversy? Stay tuned… Unravelling the Windsor Knot: Part 1 | Part 2

The Supreme Court and DOMA\’s SoberRing

Last week we celebrated the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) striking down Section 3 of the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). And let’s be clear, SCOTUS did not strike down DOMA; it indeed gutted the act, but strike it down completely it did not. The expanding and subtle rant about that is slightly further down, in this uncommonly lengthy article – consider yourself forewarned, but we need to be clear that DOMA is still congressional law. Now, we’ve all seen it on TV: The witness can only answer ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ and is asked a question where she must answer ‘yes,’ but the ‘yes’ is only because of mitigating facts that may or may not come to light. Well, I must admit that while I am assuredly a liberal Democrat who disagrees with most of Justice Scalia’s Opinions and remarks, I must say “yes, Your Honor\” to Scalia’s dissent regarding an “argle-bargle” opinion. United States v. Windsor was poorly written and the final holding was the mother of all judicial disclaimers. BUT this isn’t TV, so I get to share the mitigating facts behind my agreeing with the Justice who so often ruffles my feathers as I work through this Opinion\’s analysis. Fasten your seatbelt… Immediately in the introductory paragraph, we’re given a slight hint about the parameters of the decision when we’re told that Windsor is challenging DOMA’s provision that defines marriage. Next, in the Opinion’s Section I, we’re told flat out, DOMA’s Section 2 hasn’t been challenged here. Mitigating factor #1: Since the Court doesn’t go on to mention a sua sponte action, whereby the Court can on its own inclination consider the entire statute, we’re on notice. Only part of this despicable law is going to be decided by this Opinion. Sidebar: For those of you unfamiliar with Section 2 of DOMA and who haven’t read the Opinion, Section 2 provides that a state can refuse to recognize same-sex marriages legally performed in other states. The Court then explains that the definition provision in Section 3, which defines marriage as “only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife” and confines the term “spouse” to a heterosexual marriage, doesn’t prohibit States from allowing same-sex marriages but it does put a sincere damper on the availability to LGBT married couples of the more than 1000 benefits provided to straight married couples. One of those benefits, upon which the case\’s issue was based, is the right to the spousal estate tax deduction. Yet, even before reaching the case\’s factual issue, the Court had to address whether this case was, in fact, a case. Long ago, it was determined that courts, including SCOTUS, should only hear cases that represented a controversy. Here, there was a question on whether a controversy existed because the Administration agreed with Windsor, the plaintiff. If the government agreed with the plaintiff filing suit against it, then where’s the controversy? In Section II of the Opinion, the Court agrees that a taxpayer’s grievance should be concrete, persistent, and redressable, and that Windsor’s loss of more than $360,000 fit the bill. We all did, even the U.S., so again, where’s the controversy? Who on the U.S. side will be hurt if the U.S. agrees Windsor was hurt? Well, after discussing the issue of regular Article III standing, where a party has to meet those 3 elements mentioned above for it to be a party to a controversy and the ethereal issue of “prudential standing,” the Court finally unveils the interesting idea. It deems that the U.S. Treasury will be harmed because were it not for the lower court’s 0rder to pay the refund, the U.S. Treasury would be $360,000 richer. In other words, though the U.S. agreed with Windsor on principle, because the order for it to pay up put the U.S. government in harm’s way, we have controversy. I’m scratching my head, but we got there… Many questioned the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group’s (BLAG) right to stand in the controversy, too, but the Court stated that BLAG’s “sharp adversarial position” when considered with the guidance that would be missing from 94 districts across the country and the 1000 laws, rules, and regulations affected, the Court decided in its “prudential” wisdom that BLAG had standing. Several colleagues are still combing the lines of the Opinion’s Section II about that prudential standing stuff, but I prefer to move on to Section III, which is equally, if not more fascinating… In Section III, the Court unravels (?) its reasoning for striking Section 3 of DOMA while maintaining Section 2, the States’ power. Citing Sosna v. Iowa, the Court reasoned that in addition to the lack of discrimination espoused by the Court’s ruling in Loving v. Virginia, which make state definitions of marriage constitutional, states still have the authority to regulate marriage. Once more? A state\’s definition of marriage must adhere to non-discriminatory rules of the U.S. Constitution but the States can determine how that definition plays out. Fascinating. To further elucidate this point, the Court then cites In re Burrus for the rule that all domestic relations regarding a family fall within the legal purview of the States, not the federal government. When the government does something like define marriage, the federal courts generally defer to the States and choose not to hear domestic relations cases. So if a state’s regulation of a constitutional definition of marriage violates the constitution, the courts can look away? Remarkable. Understanding the confusion this section must have wrought, the Court then makes grand gestures: Citing Romer v. Evans, the Court provides that (1) when a law discriminates so blatantly, its constitutionality should be scrutinized; (2) unlike typical laws passed by the federal government to eliminate discrimination, DOMA does the opposite – it’s Fifth Amendment constitutionality must be questioned; and (3) states provide for same-sex marriage because marriage is much more than a myriad of legal rights and benefits – marriage confers a relationship status

The Supreme Court Ruled for Love

Last year, near this time, in our series on \”Love & the Law,\” we questioned whether the U.S. Supreme Court would embrace love again. The answer, a year later, is \”Yes.\” Today, June 26, 2013, the Court ruled that Section 3 of the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), defining marriage as a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife, was unconstitutional. Still, as many of my colleagues have pointed out the Court did not rule the entire act unconstitutional. And while some may consider a gut rehab, a complete do-over, it is not. Questions go unanswered about states that still have mini-DOMAs on their books and states that have Civil Unions or Domestic Partnerships but don\’t provide same-sex marriages. But for now, we\’ve decided to postpone the legal analysis for a week and savor the celebration. It\’s a wonderful testament to love and a befitting ruing for Pride Week. Score one for love.